For much of the last decade, global leaders in business, government and the non-profit world have been sounding a loud alarm about a mounting youth employment crisis. With good reason. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), there are about 71 million unemployed 15-to-24-year-olds around the globe, many of them facing long-term unemployment. This is close to an historic peak of 13%.

Nearly every country in the world grapples with this challenge, but it hits low-income countries especially hard. And even where there is work, much of it is low-paying. The ILO estimates that about 156 million (or 38%) employed youth in emerging and developing countries were living in extreme or moderate poverty in 2016 — equivalent to less than $3.10 per day.

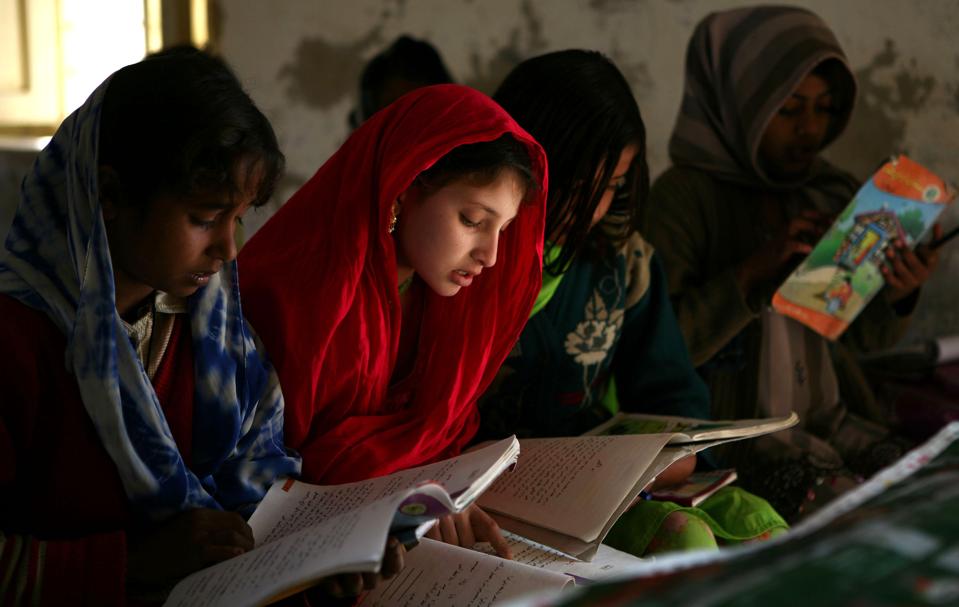

Children read from their books at a primary girls school in the Khairo Dero village in Larkana, Pakistan, on Wednesday, Jan. 23, 2008. Pakistan is seeking to sustain growth in a country where the government estimates a fourth of the population lives in poverty, or on less than a dollar a day. Photographer: Asim Hafeez/Bloomberg News

Without work experience and income, these young people are vulnerable to a lifetime of continued poverty. Desperately searching for a more promising future, they migrate to other countries where they will likely also struggle to find work and a better life. Their plight also has major implications for national companies and global businesses seeking to expand or invest in frontier markets that hold economic promise. Chronic youth unemployment puts a brake on national economies, and the lack of a literate and skilled young workforce limits businesses’ ability to generate higher growth, better profits and more jobs.

Furthermore, businesses’ ability to innovate and modernize is inhibited when so many young workers don’t have the skills they need to succeed in increasingly automated workplaces. As the International Commission for Financing Global Education Opportunities reported last year, about 40% of employers worldwide find it difficult to recruit people with the skills they need.

It will be difficult to narrow that skills gap – especially in developing countries – so long as there are hundreds of millions of children who never receive even a primary school education, or get schooling of such poor quality they don’t really learn what they need to know. That’s the much quieter – too quiet – crisis lurking behind youth unemployment. Global businesses and other major private sector institutions have a big stake in helping turn it around. Responses to the global education crisis have for too long lacked the great urgency and resources necessary to solve it.

Shockingly, for example, donor aid to basic education in developing countries has dropped by more than 14% in real terms between 2010 and 2014. The good news is that we know what it will take to get more of these students into school. This is at the core of the work of the Global Partnership for Education:

Focusing on girls. There’s abundant evidence that educating more girls leads to remarkable social, economic and health gains – and it can do much to reduce youth unemployment. But, in spite of good progress over the last decade and a half, there are still about 61 million girls not in primary or lower-secondary school and two thirds of the world’s illiterates are women.

Educating especially during crisis and conflict. About 75 million children ages 3 to 18 live in countries facing war and violence and need educational support. Children living in crisis and conflict are more than twice as likely to be out of school compared with those in countries not affected by conflict; similarly, adolescents are more than two-thirds more likely to be out of school. Let’s ensure these kids can continue learning – even during times of crisis.

Ensuring quality learning. Too many children – about 250 million — either don’t make it to grade 4 or do so without acquiring basic reading, writing and math skills. We need to address this learning crisis – urgently.

Investing in early childhood care and education. Cognitive development and learning in the first five years of a child’s life is crucial to ensure a strong foundation for learning. A growing number of developing countries understand this and are expanding early childhood education, particularly for children from the most marginalized communities.

Committing to a step change in funding. The greatest challenge facing global education is a lack of investment, a concept the business community understands well. According to the Education Commission, investment in education needs to increase from $1.2 trillion per year today to $3 trillion by 2030. The great bulk of this will need to come from developing country governments themselves, but help from major donors, including the private sector, is also important.

That, to be sure, is a big leap, especially as governments – industrialized donor countries and development countries alike – are straining to meet so many other needs within their borders and around the world. But without this new level of investment generations of children will miss out on the education they deserve – and the repercussions will reverberate around the world.

Source:-forbes